My anodized aluminum reel parts have mostly been undyed, that is, clear anodize. I did try out some dyes (23 April 2012) and even produced a reel with black end plates (9 May 2012). Other than black, I did not like the dye colors that I got. Leroy’s comment on the dye sample post was that it takes some experimentation to get lighter colors to work right.

But I also found that I would need a larger vat to sucessfully dye, so that parts could be hung vertically to not trap air bubbles. It seems to me a big problem to maintain a larger vat at the required temperature, 140 deg F.

Not long after this effort, Alan showed me his Bougle reel with a nicely colored spool (26 May 2012). He described the color as “champagne”. I found it difficult to capture the color in photographs.

Then I came across a reference to a process for anodized aluminum called “electrolytic coloring”. This article, an advertisement by a supplier to the commercial anodizers, said that their coloring electrolyte could produce bronze colors from “champagne to black”, dependent on process time. Maybe this is what Hardy used on reels like Alan’s. The electrolyte is a proprietary formulation, available in 42 gallon drums. Probably not suitable for a hobbyist like me. I found no information on DIY electrolytic coloring on the web, only that the process is also known as the “two step” process, wherein the first step is a conventional anodize using a DC power source, and this is followed by a second process with coloring electrolyte using AC power.

There is a comprehensive reference book on anodizing which I used as the basis for an earlier post (3 March 2012). When I borrowed the 5th edition through my local library, I did not connect with any information on “electrolytic coloring”. I now think that the info was there, but in a chapter titled “Anodizing in Architecture” that I did not bother to read. So when I recently visited relatives in the Champaign IL area, I made it a point to visit the U of I Engineering Library, where I found the 6th edition of the reference book. And there I found enough info to get me started.

Some points about electrolytic coloring:

1. What is added to the porous anodize layer is not dye molecules but heavy metal ions/atoms. Tin for bronze shades, copper for red, molybdenum for blue, etc.

2. The coloring process immediately follows anodizing, before sealing.

3. The metal atoms travel to the bottom of the pores in the anodize layer and so make a more durable color than dyes, whose molecules stay in the tops of the pores.

4. A long process time with almost any metal ion/atom will produce black. But at this point, the pores have been filled from bottom to top and may be difficult to seal. (Sealing is hydrating the aluminum oxide so it expands and forces the pores shut at the tops.)

5. This process is done at room temperature.

6. An AC power supply is used, low voltage. While the voltage waveform may be sinusoidal, the current waveform is not. Half cycles of current in one direction are larger than the half cycles in the other direction. This provides the necessary “throwing” of metal ions into the anodize layer.

7. When designing an anodizing cell, we don’t have to be concerned with the shape and placement of the cathode. This is because all the resistance of the cell is in the anodize layer, causing the electric field to be uniform over the entire anode. The oxide layer will grow uniformly. Not so with coloring. Significant resistance is in the electrolyte (as in plating) and the electric field will not be uniform unless some attention is given to the design of the counter electrode. Variations in color intensity can occur.

8. The rack (anode support) in an anodizing cell can be titanium, but only aluminum should be used in a coloring cell.

My initial effort is to color the spool ends of a newly designed reel. What appears to be the challenge is “racking”, which is arranging the anode support and electrical connection inside the anodizing cell, and later in the coloring cell. We need to carry over the electrical connection from anodizing to coloring because we are growing an insulating layer on the part. The only place to electrically connect to a spool end is its bore.

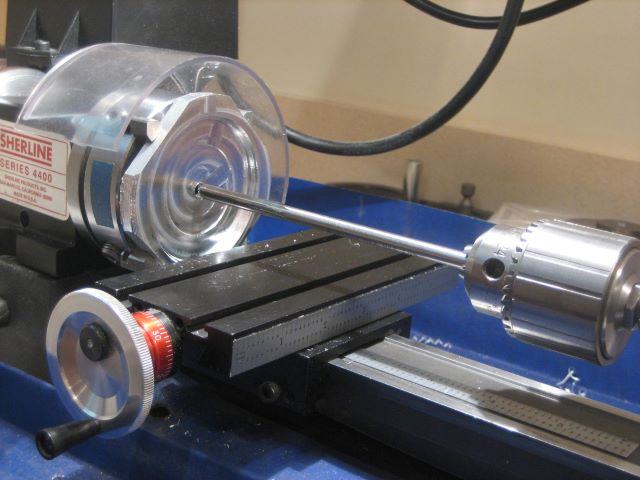

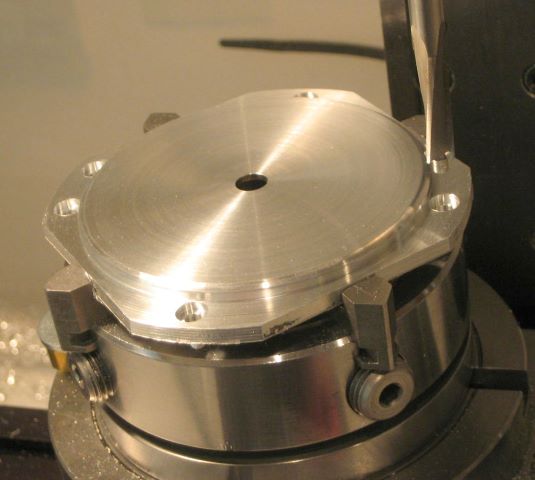

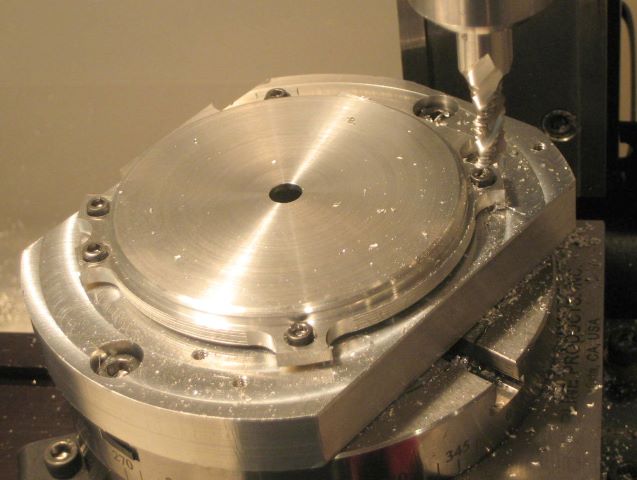

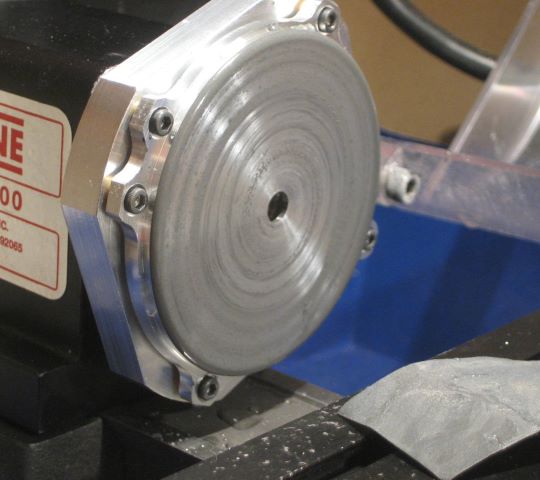

So here is the cover of my anodizing cell, with a faux spool end (i.e., a simple disk of aluminum) held by an expanding (spring) mandrel. The main post of the rack is titanium, but the last piece connecting to the disk is aluminum. This aluminum part will also become anodized and colored in the process. The cathode here is my “water cooled cathode” of the blog post immediately preceding this one.

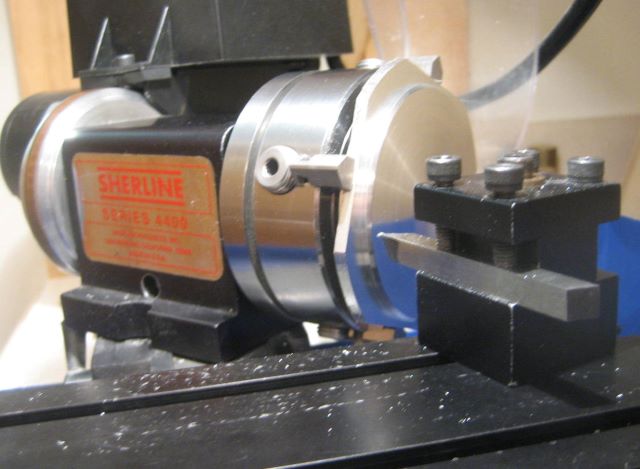

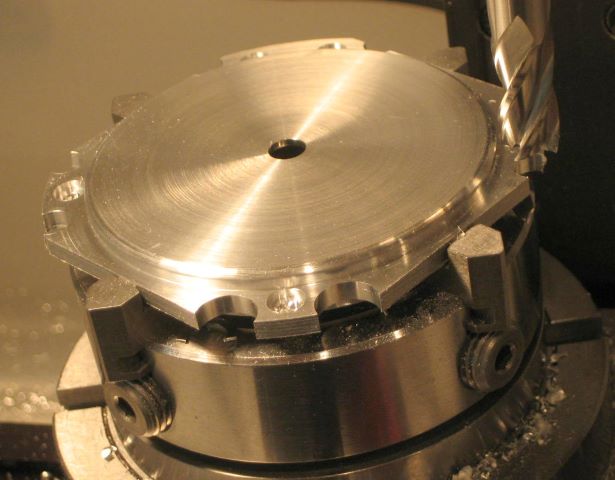

And this is the cover of the coloring cell, with the same disk and mandrel in place.

Note the two donut shaped counter electrodes. I expect these to impress a uniform electric field on the spool end/disk.

This is my AC supply, a variac and a doorbell transformer.

The variac is needed; I want 10 VAC but the “16 volt” transformer actually puts out 22 volts at no load. And I don’t know what current to expect.

Here we see coloring in process. Ambient temperature on this day was 80 deg F, so I used a cold water bath to get the cell down closer to 68 deg F.

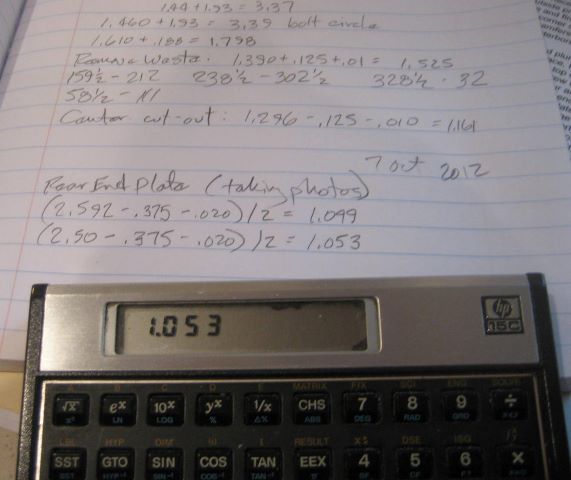

My process parameters:

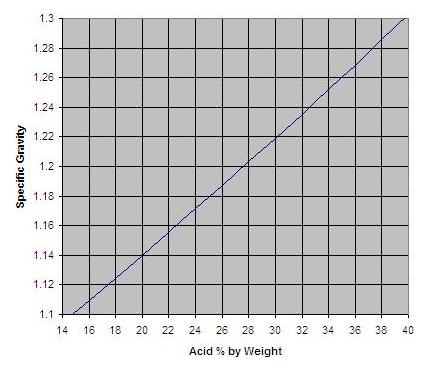

Electrolyte is 10 g/l stannous sulfate plus 20 ml/l concentrated sulfuric acid. Balance is distilled water.

Run cell for 5 minutes at 10 VAC.

I was able to extract this information from the reference book and use it directly without having to do experiments.

My cell holds 24 fluid oz., so I used 7 grams of SnSO4 and 40 ml of battery acid (35% H2SO4) in one batch.

In this solution, the stannous sulfate is the source of tin ions, and the (mild) sulfuric acid attacks the anodize layer to allow electrical conduction.

Stannous sulfate has several advantages as a coloring agent, but one big disadvantage: the “stannous sulfate readily oxidizes to stannic sulfate” and then precipitates out of solution. I have no idea how long this takes. The proprietary part of commercial coloring electrolyte is the stabilizer, which keeps the tin in solution. By now, I can say that my solution is good for at least several hours.

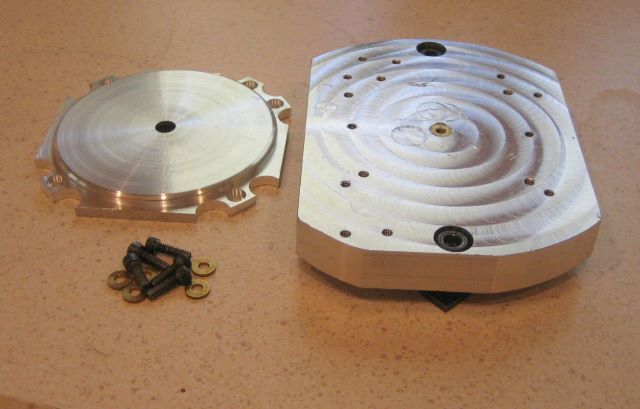

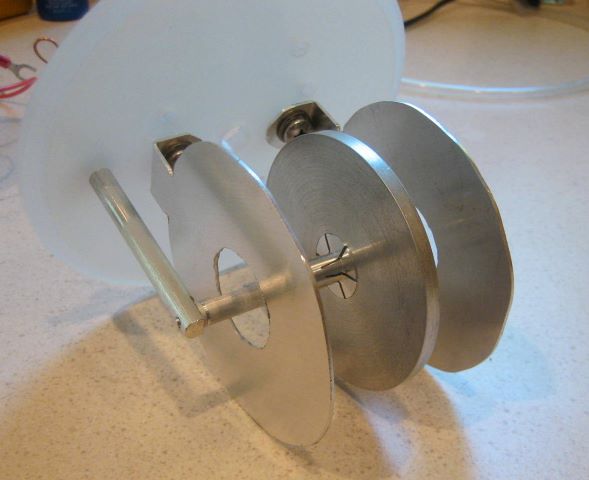

I did have one problem. My initial spring type mandrel did not provide a reliable contact for the anode. It worked the first time, but apparently I did not clean the part well enough and there was a streak of discolored surface. So I stripped off the anodize layer with lye and re-did the whole process. The second time through, anodizing was successful but the spring mandrel lost contact with the disk when I transferred to the coloring cell. The mandrel became colored but the disk did not. Here is a view of the spring mandrel, which I now think is not a satisfactory design.

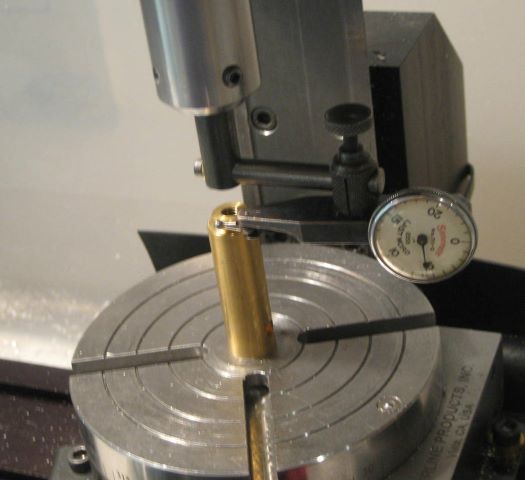

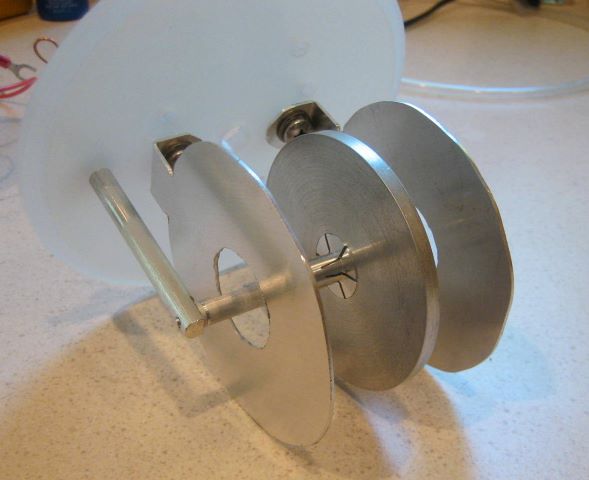

This is my improved design. The split ring fits into the bore of a spool end. Its inner diameter is axially tapered, exactly fitting the taper on the other part. These two parts are easily locked into the spool end bore with an arbor press.

Below is a successful coloring of the test disk.

The surface area of disk and mandrel together is 14 square inches. During coloring, the AC current settles at 0.24 amp, after an initial surge of 0.75 amp. At different angles, the disk appears to have different coloring shades. This coating not like a dyed coating. I still find it difficult to get satisfactory photographs of the coloring.

Finally, here is a spool with colored end plates.

Update 1 Oct 2012: I tried using a mixture of zinc sulfate and stannous sulfate, which is supposed to produce gray instead of bronze. But it was a bust. I still got “bronze”, and the coloring was uneven.

I was able to buy stannous sulfate from an Ebay vendor, as a lab reagent.

Another possible source for coloring electrolyte is Caswell. They sell a tin plating solution that is based on stannous sulfate. And, it includes stabilizer so the solution can be saved and re-used. It would need some added sulfuric acid.

Update 15 June 2020: I bought a 500g bottle of Tin Sulfate in 2012, and it worked for the next two years. Then I left it in a cabinet until now. I find that it has degraded and can no longer provide coloring.