First of all, I must say that the pawl test data that I previously posted (Aug. 22, 2010 : Results of Pawl Wear Test) cannot be relied upon. I now realize that the “gearmotor” that I used for this test may have been misoperating. This post explains why the data is suspect.

Yesterday I intended to start more ratchet/pawl wear tests. I made a new ratchet. As I fastened the new ratchet in place, I noticed that I could manually turn the output shaft of the gearmotor in one direction, but not in the other. This is peculiar behavior for a gearmotor. Then I engaged a pawl and plugged the motor into an outlet. To my surprise, the gearmotor did not rotate, but did make its usual buzzing sound. I unplugged the cord, wrenched the output shaft around a little, and plugged the cord back in. This time it rotated, but stopped after a few seconds. Time to find out just what this “gearmotor” is.

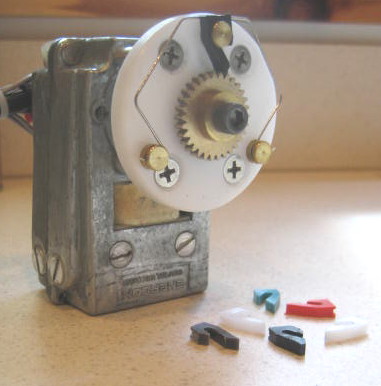

Here is a view of the inside parts of the motor.

Around the shaft are two sprag clutches. Each is fixed to a moving magnetic armature with limited rotation, and each armature has two springs that push it toward a central position. (These two swinging armatures stack axially on the shaft and are difficult to see in the photo.) A separate fixed armature part incorporates a ceramic permanent magnet. Under 60 Hz excitation from the coil, the two moving armatures vibrate in phase opposition (?), and the two clutches cause the output shaft to turn (at least some of the time).

The problem with the wear data that I have already posted is that I cannot be certain that the motor was turning throughout each of the six day tests. The sprag clutch drive now operates intermittantly; I cannot say how long it has been this way. Certainly the motor did work part of the time, or no wear would have occurred with any of the materials. The Delin pawl that shows zero wear was not the last one tested.

In retrospect, I can see several reasons to have had earlier suspicions about of the “gearmotor”. It was the cheapest and most compact gearmotor available (too cheap, too compact to be real). It made a humming sound that I would not expect from gears meshing, and with time, the sound became a buzz that gradually drown out the sound of pawl on ratchet.

I do know that I was getting rotation at the start of each test, and I may be overly cautious in now declaring the data to be suspect. But it bothers me that the wear results obtained have no correlation to material properties. It would be much more satisfactory if wear lined up with coefficient of friction, or perhaps with hardness.

So there is nothing to do now but obtain a real gearmotor and repeat the tests.