When milling the profile of a raised pillar end plate, I screw the work to a tool plate. For the first two raised pillar reels that I made, I used a tool plate that I originally made for milling S shaped cranks. It is 3.5 inch diameter and about 3/4 inch thick. I was able to add 5 holes near the periphery to secure the reel end plates.

The problem with this tool plate, however, is that the work covers the two screws that clamp the tool plate to the rotary table. This causes problems because it is then difficult to register the rotary table angle calibration with the existing pillar holes.

So I have made a new tool plate from 4 x 3 x 1/2 inch aluminum. This leaves space for me to tighten the clamping screws with the work already screwed down. I can get the registration that I need to continue with the profiling.

Here you see a partly made end plate on top of the new tool plate.

Like other tool plates that I have made for the rotary table, there is a pilot on the back.

The tool plate requires many holes, accurately located. When I first started drilling this one, I followed my usual practice of holding the center drill in a Jacobs chuck. But there was a large vibration due to the inherent centering inaccuracy of such a chuck. It came as a revelation to me that center drills really should be held in collets, which are much more accurate. After all, center drills are made with shanks of standard fractional inch sizes (1/8/, 3/16, 1/4, etc) for which standard collets are available.

A related revelation was the reason why this set of tiny drills was made with 1/8 inch shanks; it allows them to be held in a standard collet. A tiny drill will not survive off-center driving.

The many holes then need to be tapped. This operation goes much more quickly with a “gun tap” (a.k.a. spiral point tap) that drives chips forward instead of into the flutes. By using 1/2 inch material instead of 3/4, it was easy to through drill the plate, allowing me to use a gun tap. The many holes are 4-40.

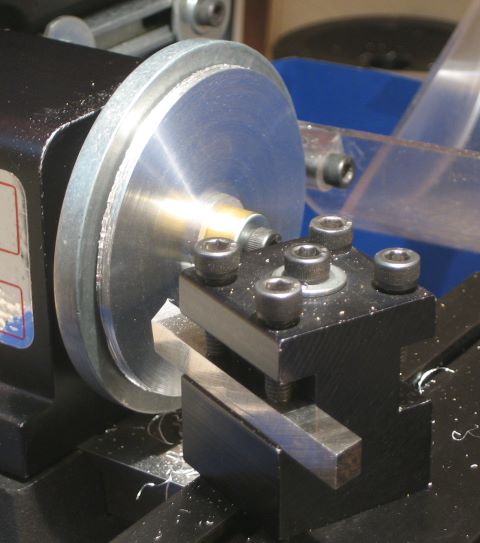

Here is a view of the tapping operation. A pin, held in a collet, pilots on the upper end of the tap wrench, thereby preventing side loads and tap breakage. In this case the collet is not needed for centering accuracy but to save vertical height. A Jacobs chuck, even 1/4 inch, would not have also fit into the limited height of this Sherline mill.