This article appears in the July/Aug 2015 issue of the newsletter The Planing Form. The originator of the newsletter, Ron Barch, has retired but the newsletter continues under Kirk Brumels.

Ferrule Shrinking

At the Grayrock 2014 gathering, I was quizzing Jed Dempsey about ferrule repairs, particularly about fixing a loose ferrule fit. Jed had seen tools that applied pressure through rollers to the OD of a female ferrule, and he described them as “like a tubing cutter, but with a third roller instead of a sharp wheel”. I like gadgets, this intrigued me, and I had to see if it actually worked.

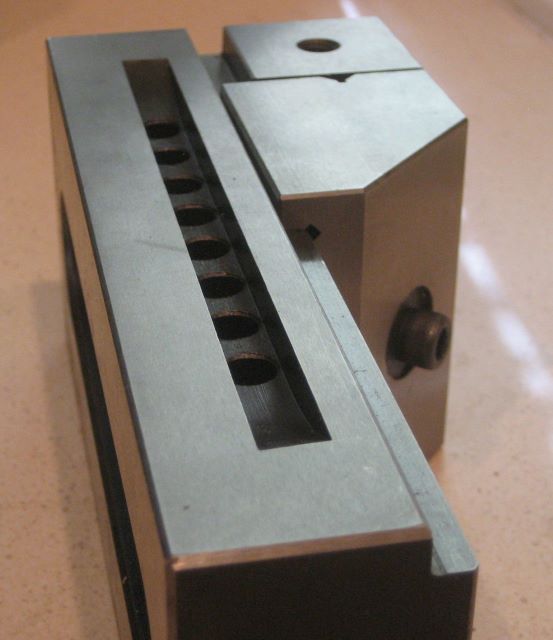

My Ferrule Shrinker

I have a small mill and lathe (Sherline). So I designed this tool as something that I could make with my limited resource. It is not like a tubing cutter; that approach seemed too complex.

I thought it would be a good idea to make the rollers as large as possible, in order to get the most hoop stress with the least contact stress. So I chose 7/8 inch diameter ball bearings to be the rollers. These will close down onto a diameter of .140 inch, small enough to do work on a “size 8” female ferrule.

To tighten down the rollers requires adjustment of two screws instead of just one; this is the price of simple construction. But I don’t think that it is a major disadvantage.

History

Once I understood that the tool did indeed work, I quizzed Jed some more to find its origin. Jed pointed to Dave Male, and Dave says that it is the idea of famed rodmaker Wes Jordan, during his time at Orvis. The original purpose was to flex a stuck ferrule set to help break it loose, but soon after it was found that female ferrules could be reduced. This origin is probably in the 1950’s.

This picture, provided by Chris Bogart, is what I believe the older ferrule tools to be.

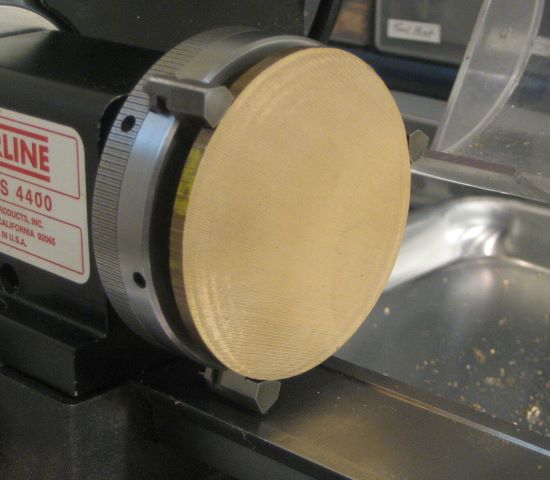

How to Use the Tool

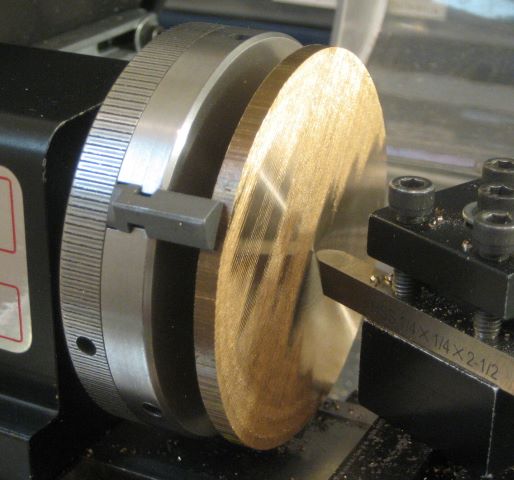

Insert the ferrule and tighten the two radial screws equally, by feel of your wrist, and then turn the tool around the ferrule several times. Remove the tool and trial fit the ferrule set. Be quite careful at the start because if you go too far, you will end up having to re-lap the male ferrules. It is a trial-and error process, and I usually do not get permanent set of the female on the first two or three attempts.

Do not set the rollers on top of the moisture plug; that is a rigid point on the ferrule and cannot be spun down. It is the same with the welt. I stay back from these by 1/32 or 1/16 inch. The width of my rollers is 11/32 inch, so you may want to do separate rolls at two locations on the ferrule.

I have worked on both brass and nickel silver ferrules, and it took much more time to reduce the brass.

How to Make the Tool

I include these instructions for the benefit of home shop machinists with time on their hands, but I am also having several tools made to sell to guys who just want to get on with the main task of fixing ferrules.

The parts are:

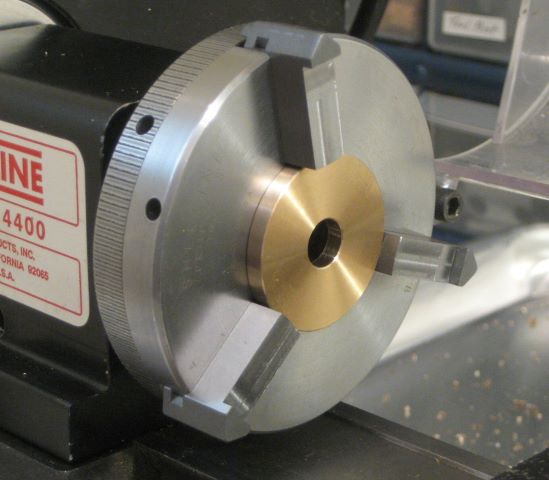

1. Three ball bearings, 7/8 OD by 5/16 bore by 11/32 wide. I chose double sealed bearings only because they were a little wider than other types.

2. Three short pieces of precision ground shaft, which will press fit into the bearings. Make proper press tools so that you do not press on the outer races of the bearings. Example material : McMaster-Carr 1327K73.

3. Five screws, 10-32 by 1.25 inch.

4. Three washers. I made thick ones to take up excess screw length, but you might decide to use standard washers and just make the plates thicker.

5. Three spacers 0.5 inch OD by .350 height and drilled to clear a #10 screw.

6. Two round side plates of aluminum alloy, machined per the drawing.

This drawing states no tolerances on the dimensions; rely on your common sense. The main problem is to ensure that the device can be assembled, and this requires precise alignment of two holes (5/16 diameter) and one slot (5/16 wide). To get this alignment, I screwed the two plates together and then made the 5/16 holes and slot.

(Article ends here)

Since writing this article, I have sold a number of tools by way of a classified ad on Clarke’s Forum. Email me if interested; my address is in the “About” section of this blog.

The batch manufactured tools are a little different from my prototype. The heads of the three axial screws are recessed in counterbores, and the five screws are 1 inch length instead of 1.25 .

Additional Information for Owners of the Tool

The fit of the dowel pins into the the bearings is a medium press. Do not attempt to remove or install bearings from the pins without proper press tooling; i.e., do not apply force to the outer races of the bearing because you will “Brinell” them.

The fit of the dowel pins into the aluminum end plates varies from light press to close clearance. If you remove the 3 axial screws, the assembly may or may not slide apart. In the latter case, you will have to “jack” the plates apart. To do this, first pull out the three spacers. Place the tool face plate (countersunk side) down on a bench. Thread the 3 screws into the back plate (tapped side). Cover the 3 bottom side clearance holes with pennies and evenly turn down the 3 screws, pushing the two plates apart.

If your tool has a light press fit of the 3 dowel pins, you may find, upon re-assembly, that one or two bearing outer races drag against the inside surface of one plate. Use an arbor press to center the bearing between the plates.

Update 12 Nov 2017:

The tool is not suitable for shrinking male ferrules because the tip end of the male will not roll down. Fix male ferrules in the usual way, by abrasion.

If your ferrules have been blued, the bluing will probably not survive rolling. Plan on re-doing the bluing.

There is no need to remove the ferrule from the rod while it is worked.

See also my earlier article:

Ferrule Shrinking

Also note that this blog has a page “Ferrule Shrinking” with ordering information.